In general, when I’ve given the diagnosis of “pneumonia” to a patient, a look of seriousness comes over them. Yet, when I’ve given the diagnosis of a “chest infection” to another, they seem half-expectant.

So, the question is, what is the difference?

The answer is, sometimes, none.

The term “chest infection” really isn’t a technical medical diagnosis. Rather, it’s a simplistic statement that is usually used to describe a “lower” respiratory tract infection.

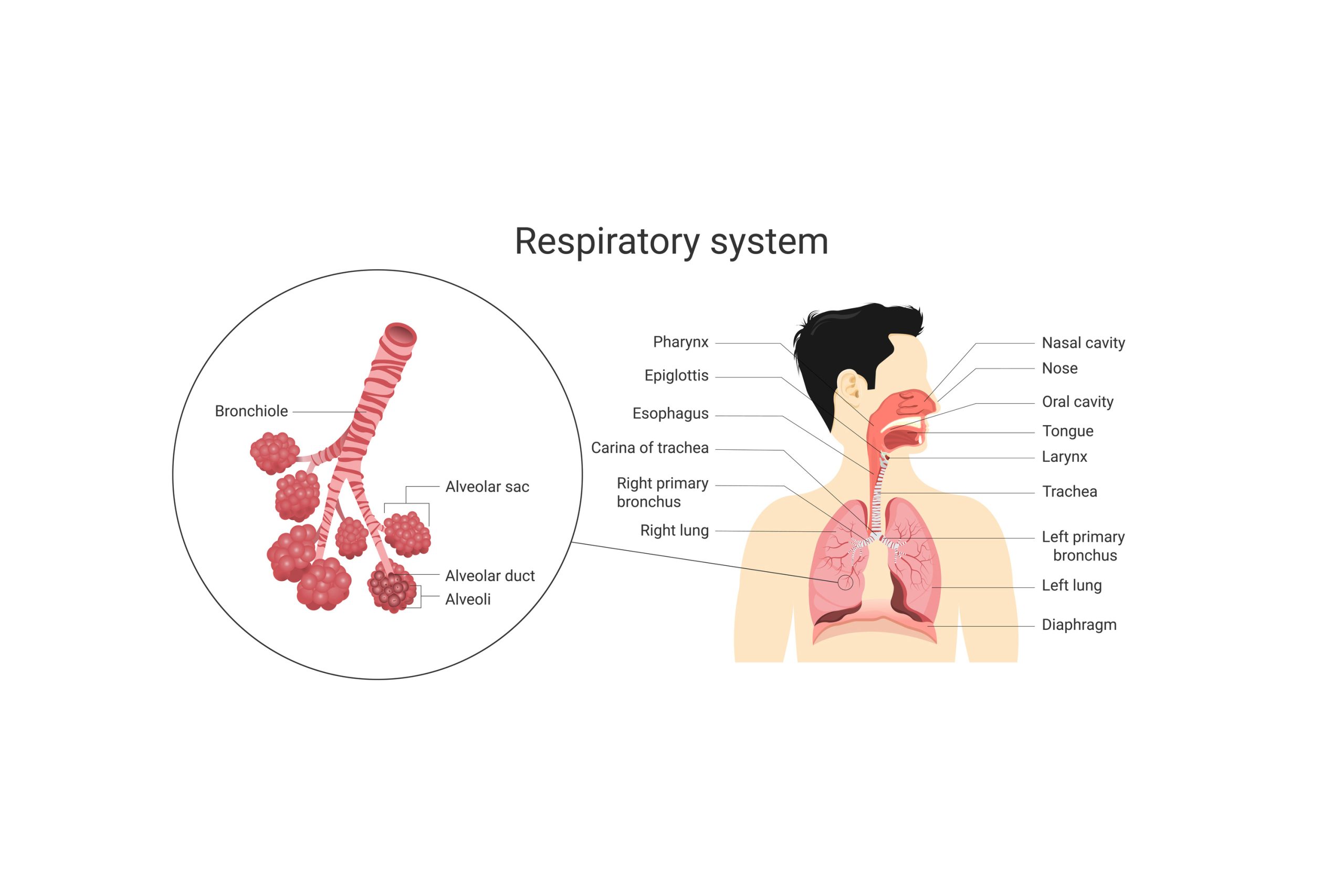

Let’s look into this further. The respiratory tract begins from a person’s nose. Infection can occur from anywhere starting at the nose, all the way down to the throat, and this is termed an “upper respiratory tract infection”. So, tonsillitis for example, is still considered an upper respiratory tract infection, or URTI for short. The voice box, technically termed the larynx, usually marks the deepest part of the upper respiratory tract. If you ever lose your voice because of infection, you’re said to have “laryngitis”. This is usually caused by a virus. Like tonsilitis, this is described as an upper respiratory tract infection too.

Beyond the larynx is the trachea. Infections of the trachea all the way into your lungs are termed a lower respiratory tract infection, or LRTI for short. The trachea divides into two main branches, the left and right main bronchus, and after successive smaller branching, we get the air-filled sacs in the lungs, called “alveoli” that really are the functional unit responsible for the transfer of oxygen and carbon dioxide between your body and the air you breathe.

It’s worthwhile pausing here to remember that some disease processes can involve both the upper and lower respiratory tract, and also that one can lead to the other. For example, some people can get a very sore throat and lose their voice, with some associated difficulty breathing. This is called laryngotracheobronchitis. It is usually viral, but can be bacterial. Other times, the flu can cause a runny nose and sore throat and go on to cause infection all the way into your lungs to the alveoli, this is more rare.

Coming back to the question we asked at the start then, what is the difference between a chest infection and pneumonia? Pneumonia is referring to specifically any infection that has gotten so far down, right to the depths of your lungs so as to affect the terminal branch, those little air filled sacs responsible for gas transfer, the alveoli. By contrast, “a chest infection” is a more colloquial reference to a lower respiratory tract infection beyond your neck really, in your chest cavity. So that could be affecting your bronchi or any branches beyond, perhaps even down to the air filled sacs, the alveoli. So, when your doctor says chest infection, it could in fact mean you have pneumonia. It’s hard for a doctor, listening to the lungs of a patient, to be so sure after all, exactly what level an infection has definitely gotten to. Hence the reasonably common use of the general term, “chest infection”.

If your doctor does say that you’ve got pneumonia, it may not be all doom and gloom. Pneumonia itself can vary in cause and severity. It can be caused by viruses (influenza, COVID-19), fungi or bacteria and can be mild or severe.

The symptoms of severe pneumonia include:

- Fever, shakes and shivers

- Difficulty breathing and shortness of breath

- Loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting or diarrhoea

- Sharp, stabbing chest pains, particularly when you breathe in

- A cough with thick, coloured or bloody phlegm

People at risk of getting and having more severe cases of pneumonia include infants (under 2 years of age), people over 65+], and those with suppressed immune systems.

What should you do if you think you’ve got a “chest infection”?

1. See your doctor. If you feel like you have a cough with any breathing difficulty, or chest pains, and therefore think you may have a chest infection, it’s worthwhile seeing your GP to be examined. Please remember, however, to do a RAT test first, to make sure you don’t have COVID-19.

2. Antibiotics? If your doctor decides you may have a bacterial infection, then they may prescribe antibiotics. Note that antibiotics do not treat viral infections.

3. Antivirals? If you get COVID-19 and fulfil particular Government criteria, you may be eligible for antiviral medication. So, in general, if you get COVID-19, arrange a telehealth consultation with your GP, and they’ll guide you about this.

4. Steroids? When you get pneumonia, your lungs get very inflamed. Whilst at some level, the processes involved in inflammation are protective and there to fight infection, severe inflammation itself can restrict your breathing and worsen your condition. In this case, you may experience increased shortness of breath and wheezing. Your doctor may then prescribe a steroid such as prednisolone which has a strong anti-inflammatory action.

5. Deep breathing and coughing exercises. Often the parts of the lungs that are susceptible to infection are the very bottom, the “bases”. These parts tend to collapse easily, even ordinarily, since they’re only forced open by deep breathing. To get these parts open, moving again and avoiding collapse, doing slow deep breathing first thing in the morning and at night can be helpful. Coughing up any phlegm, to expel it, can similarly be helpful. There is a technique called the “huff cough” that physiotherapists use, for this purpose. The general gist though, better out than in!

6. Drink fluids. If you’ve ever been in hospital, often you are put on a “drip” to hydrate you directly via your veins rather than (or in addition to) fluid that you’d ordinarily drink. Similarly, as noted in the above point, the physiotherapist may see you, to help you with breathing exercises. Do these things at home, deep breathe and drink fluids. Getting dehydrated always makes being unwell worse. When you get dehydrated, your blood literally gets thicker, increasing your risk of low blood pressure (which may make you dizzy and fall over), blood clots in your legs, stroke, having a heart attack or kidney failure. Dehydration also thickens the phlegm in your chest, making it harder to cough out. Keep drinking fluids to avoid such complications. Note that some patients, for example with pre-existing heart conditions, may have a fluid restriction. Such patients should consult their doctor about how much fluid to drink.

How do I avoid getting pneumonia?

- Diet. Eat healthily, including lots of fruit and vegetables. In particular, lots of fruit with vitamin C and citric acid such as oranges, strawberries, kiwi fruit, passionfruit, lemons and pomegranates. Make sure also that the iron level in your blood isn’t low. Iron is an important part of your immune system.

- Exercise. Like most parts of your body, the saying “move it or lose it” is true for your lungs. Regular exercise will keep your respiratory tract and system functioning well, and give you that spare capacity to better get over infections, should you get any. At the very least, remember to consider that taking time to do a little deep breathing daily will help open up those bases of your lungs, that tend to collapse, even when you’re not sick. Note that during deep breathing, you may blow off extra carbon dioxide and eventually, blowing off too much carbon dioxide, too quickly, can make you dizzy. So perhaps consider doing it whilst seated, if you’re prone to dizziness or falling over.

- Vaccination. Vaccinations against COVID-19, influenza and pneumococcal can all help decrease your risk. If you’re not sure about any of these, ask your doctor.

- Quit smoking. You need to be motivated, and then see your doctor who may be able to help you fight the cravings, such as with nicotine patches.

- Good hygiene. This includes hand washing and considering wearing a face mask, at least at particular high risk times (hospitals, crowded areas).

Like always, I hope this article has helped explain things. The main message is, if your doctor proclaims that you’ve contracted pneumonia, know that there are ways you can safely get better in the community. And indeed, know that there are definite ways you can maximise the functioning of your respiratory and immune system, at other times.

Dr Floyd Gomes

Managing Director, Atticus Health